Nepenthes 102: Morphology

Learn about the parts that make up Nepenthes - a little more complicated but worth the ride!

Roots

As with most vascular plants, all Nepenthes begin with a primary root formed during embryogenesis, which gives rise to secondary, tertiary, and higher-order roots. However, in contrast to many terrestrial plants, Nepenthes often develop shallow and relatively sparse root systems. This adaptation reflects their typical habitats—moist, low-nutrient environments—and is especially pronounced in epiphytic and lithophytic species. This can surprise new growers who are accustomed to more robust root systems in other genera or hybrid Nepenthes.

Stems

Moving up, the stem or vine of a Nepenthes is modular, composed of repeating units called phytomers. Each phytomer consists of:

A node, where a leaf attachment originates

A leaf (which we’ll examine further below)

An axillary bud, usually hormonally suppressed from developing

An internode, the section of stem between nodes

Each phytomere is produced by the terminal bud, or apical meristem.

Leaves (including pitchers!)

Like with many carnivorous plants, the structure of the pitcher evolved from a simple leaf. It is not a flower, such as the slipper-shaped pouches of Cypripedioideae (slipper orchids), or a fruit, as I’ve been surprisingly asked in the past. Nepenthes pitchers, as we all love, have evolved to trap and eat insects rather than trick or force them into pollinating.

Paphiopedilum hookerae var volonteanum -

Photo Credit: Greg Bourke

Corybas fimbriatus

Photo Credit: Garth Smith

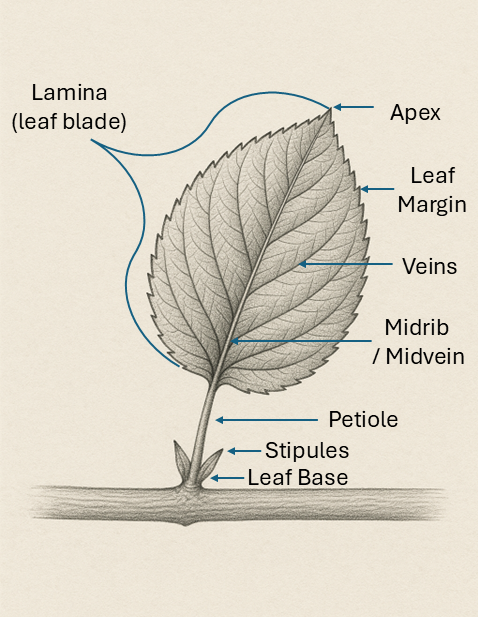

If we imagine a simple cartoon leaf we’d see:

the leaf base: the connection point of the

the petiole: the stalk attaching the leaf to the stem

the lamina: the flat leaf blade which culminates in the leaf apex or tip, and which is bordered by the leaf margin

the midrib or midvein: the main vascular structure running up the middle of the lamina, with a network of smaller veins emanating out

Leaf illustration (mine)

Nepenthes mirabilis (winged) x rowaniae

Photo Credit: Paul Beri

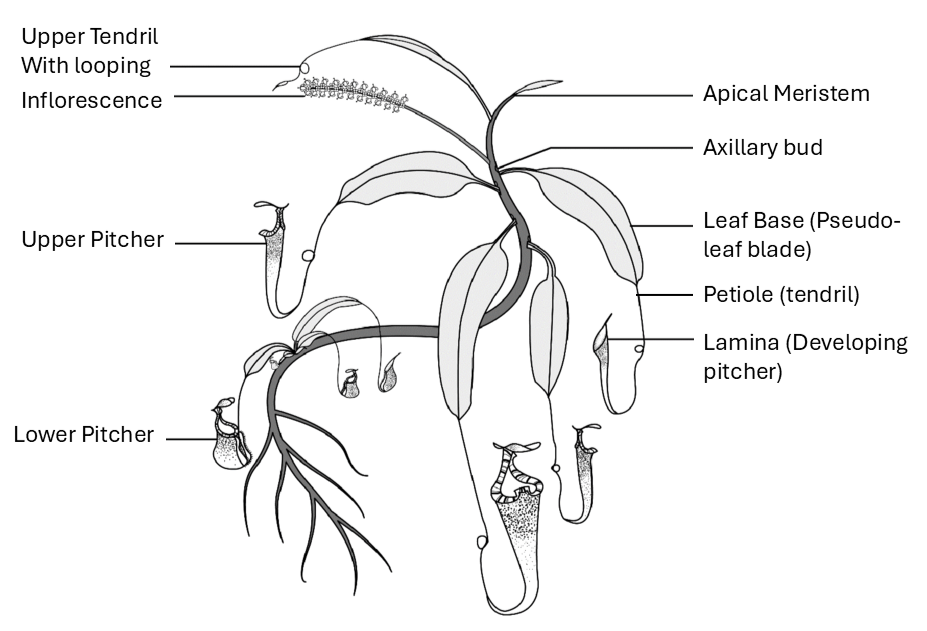

This is true in the Nepenthes but appears commonly mistranslated. Hobbyists often distinguish between the “leaf,” “tendril,” and “pitcher,” but this terminology is oversimplified and botanically imprecise. Books on Nepenthes generally replace ‘leaf’ with the more specific ‘lamina, but this is also incorrect.

In Nepenthes, the pitcher is formed by the lamina. While the lamina evolved to take the form of the pitcher, the petiole evolved into the tendril, and the leaf base evolved into the flat photosynthetic solar panel by forming a ‘pseudo-leaf blade’. The flexibility of morphology is quickly seen in the incredible ‘winged’ variations of many lowlander hybrids.

Pitcher size in Nepenthes varies dramatically between species. For instance, N. argentii produces tiny pitchers just 4 cm tall and 3 cm wide, while the enormous traps of N. rajah can reach up to 41 cm in height and 20 cm in width. Beyond size, Nepenthes pitchers also exhibit remarkable morphological diversity in shape, colour, and the structure of the peristome.

N. mollis, N. ampularia, N. muluensis, N. leonardoi, N. lowii, and N. burbidgea.

Photo Credit: Greg Bourke

In a striking example of evolutionary adaptation, most species produce distinctly different pitchers depending on their position along the vine. These are typically classified as lower, intermediate, and upper pitchers, and can vary so dramatically that they appear to be from entirely different plants. In at least some species—and likely all—this variation is thought to correspond to shifts in ecological function, targeting different prey types at different heights within the plant’s environment. However, this change in growth form can be triggered by other influences such as light and nutrients.

Flowers

Nepenthes flowers can be similarly unintuitive. Nepenthes produce inflorescences which are entire clusters of flowers. Often the entire cluster will be referred to as the ‘flower’, but this is not correct. Nepenthes inflorescences may be racemes (unbranched) or panicales (branched).

Crucially, Nepenthes are dioecious: individual plants produce either male or female flowers, not both. This means you can’t self-pollinate a single plant, though intersex Nepenthes are seen very rarely. Before opening, male flowers are typically spherical, while females are more ovoid. Once open, male flowers bear prominent anthers with pollen, while females feature a central stigma for pollen reception. Once the sex of a plant is known, identification is consistent for future flowerings.

Nepenthes spp. flowers do not produce true petals either. While many genus flowers have sepals, the leaflike flower parts that enclose the petal, and the petals themselves, in Nepenthes the tiny, four (in most Nepenthes species.) segments of the flower are actually tepals (segments with no differentiation between petals and sepals).

Flower scent varies but most are unpleasant, ranging from sweet to musty or fungus-like. The explanation for this is the range of pollinators of Nepenthes which are commonly insects such as flies, moths, wasps, and butterflies.

Morphological summary

This leaves us (pun intended) with the following recommended words to use:

Roots – for anchorage and minimal nutrient uptake

Phytomer – modular building block consisting of a node, leaf, and internode

Petiole – includes:

The stem connection

Flattened ‘pseudo leaf-blade’ for photosynthesis

Tendril for climbing and pitcher support

Lamina - includes the pitcher body, wings, peristome, spur, and lid

Glands – nectar glands (attractants) and digestive glands (enzyme secretion)

Inflorescence – the full flower-bearing structure, not a single flower

Tepals – a segment of the outer whorl in a flower that has no differentiation between petals and sepals.

These categories provide a strong foundation and can be expanded with more detail during species-level identification.

Illustration by Felicia Leong Wei Shan for ‘The Pitcher Plants (Nepenthes Species) of Singapore’. I have altered the labels to be correct as per my understanding.